By Marianne Schnall

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Dr. Jane Goodall first setting foot in Gombe, Tanzania, to begin her groundbreaking research on chimpanzees. Her work on chimpanzee behavior produced a wealth of scientific discovery, reminded us of how alike and interconnected we are with the animal world and evolved into a global mission to “empower people to make a difference for all living things.” The 86-year-old global icon, ethologist, environmentalist and UN Messenger of Peace also authored several books and founded her own organization to carry forward her pioneering work, the Jane Goodall Institute, as well as its Roots & Shoots program, which aims to encourage and motivate young people to take action on issues that matter to them in their own communities.

The last time I interviewed Jane was ten years ago on the 50th anniversary of her trip to Gombe. We talked about a variety of topics, and I remember how timeless and powerful her insights were, for example about how she felt we had lost wisdom, due to what she perceived as a “disconnect between the head and the heart.” What always struck me about Jane is even with all of the problems she notes that we face, she always holds and radiates hope, and passionately believes in humanity’s ability to evolve and change our ways.

So given all the many serious issues we are facing in this unprecedented moment ten years later, in the midst of a global pandemic, social unrest, and with devastating hurricanes and wildfires demonstrating the concerning effects of climate change, I decided to reach out to Jane for another interview for my new video series The Shift, talking to prominent thought leaders who are helping to usher in the necessary paradigm shifts to create a better world. I wanted to gain her perspective on all that is happening, as well as once again solicit her much needed wisdom and her call to action. I talked to her by Zoom, as she has been for the last several months in the UK quarantined in her childhood home, still intent on spreading her message, even if that means virtually. You will hear her call herself “virtual Jane,” as she has been doing through interviews, videos, as well as soon launching her own podcast.

No matter what topic we talked about—whether it was the connection between the abuse of animals and nature with climate change and pandemics, to what shifts in thinking and behavior need to be made to save us, to the status of women and why equality is so important, to what she hopes her legacy will be—she was reflective, immensely wise and always inspiring. Her messages offer a boost of hope and mobilization we can all use now as we live through these challenging times and try to make lasting change. As she reminds us, “Realize that it’s not you alone—together, collectively, we are making a difference. We’ve got to get together and take action now.”

Watch a highlights video of our conversation below:

Below is our far-ranging conversation. You can also watch the full interview here.

Marianne Schnall: I want to start by placing us in this historic moment where we’re facing a global pandemic, and we’re in the wake of devastating wildfires and hurricanes, which are making more real the concerning impacts of climate change. What has been on your mind as we’re experiencing these rather alarming conditions on our planet?

Jane Goodall: What’s been on my mind is how tragic it is that basically we brought all this on ourselves because we have absolutely disrespected animals and the environment. When it comes to the pandemic, we destroy habitats. We push animals into closer contact with people in some cases. This can create a situation where a pathogen can jump from an animal to a person and may create a new disease. Then we hunt them, kill them, eat them. We traffic them. We send them to be eaten or as medicine or sold as pets to the wildlife markets in Asia, we sell them in the bushmeat markets in Africa. We imprison billions of animals for us to consume in these intensive agricultural animal farms, known as concentration camps for animals. And in all of these situations, we create this perfect environment for a virus, in this case COVID-19, from a wildlife market in Asia to jump from an animal to a person.

And of course this pandemic has caused suffering, loss of life, loss of jobs, economic chaos, all around the world. But at the same time, going on for some time now, is a worse crisis, and that’s climate change. And scientists, yes, they predicted the pandemic, and for years they’ve been predicting this change in world climate and weather patterns. It’s always been the environment losing out against the need for global economic development, the bottom line, the GDP, and we can’t go on like this. We brought this on ourselves.

Schnall: Absolutely. We’ve been abusing our fellow animal friends, and I’ve heard it said that there’s “speciesism,” this sense that somehow humans think we’re superior and are more important than animals. How does that factor into this, and how can we change that thinking?

Goodall: Well, it does factor into it. Believe it or not, but in the early sixties, when I was sent to Cambridge to do a PhD, never having been to college, I’d been with the chimpanzees about two years. And I was nervous going to Cambridge in the UK and shocked when the professors told me that I shouldn’t have given the chimpanzees names; numbers were more scientific. I couldn’t talk about personality, mind or emotion because those were unique to us. But fortunately, I had a wonderful teacher when I was a child: my dog Rusty. He had taught me that, in this respect, the professors were absolutely wrong, and I was able to stand up to them. And luckily chimps are so like us biologically, our closest living relative, that with my descriptions and my husband, Hugo van Lawick, his film, science literally had to admit that we are not the only beings on the planet with personality, mind and, above all, emotions.

So that opened the gate into a new consideration, a new understanding, of other animals. So today, because science has opened its mind to this, we’re learning more and more about animal personality, animal mind, the intelligence of animals—we’re being amazed all the time. And certainly animals can feel fear and distress and pain. So all of these animals I was just talking about—the ones that are trafficked, shot, killed, eaten in the factory farms, in the wildlife markets—they are individuals with personalities, with feelings, not just animals out there. And this feeling that just because we’re eating animals, therefore they’re different, they’re not different. And pigs can be more intelligent than dogs.

Schnall: You often speak about the fact that we have become so disconnected from our environment that we don’t see ourselves as part of this integral, delicate ecosystem that of course unravels when you don’t see it that way. How have we lost touch with this, and how can we restore it?

Goodall: We’ve lost touch particularly today because so many people live in a virtual world. They’re not spending time out in nature. You know, when I was a child, there wasn’t even television, let alone computers and cell phones. I spent all my time outside watching the birds and the squirrels and the other animals, the insects. And today, kids are on their cell phones. It’s tragic because we now know it’s been scientifically proven that nature—green, singing birds, leaves, flowers—is essential for really good psychological development for young children. And it’s been also proven that if you start “greening” a very disadvantaged area of a city where there are high crime rates, as you put in trees and shrubs and flowers and birds come back, crime rates drop. So it’s just very tragic that we’ve gotten so isolated in our little bubble of making money and we’ve stopped thinking about our relationship to the natural world. And yet we can’t. We’re part of it. We depend upon it.

Schnall: One of the things I’ve been thinking about is: what is mother nature trying to tell us? What lessons can we at least learn that can wake us up during this time? Do you think that experiencing this moment where people are being affected by COVID-19 across all of these very false divides—race, class, gender, across national boundaries—can help us to see ourselves as one family here on our home, planet Earth?

Goodall: Yes, that’s true in a way, but when we think of the different access to medical treatment that different people have, there is still discrimination. It’s much, much easier for an affluent person in the United States, for example, to have access to emergency treatment than it is for somebody from a poor community, particularly if they’re Black. So this discrimination is still deeply embedded, even though the disease doesn’t care who it attacks, but it has more chance of harming the disadvantaged, I think.

Schnall: And one of the things that you just pointed out, too, because I do think this time is also really revealing all of the cracks in our systems, all of the inequities that there are. It seems like a unique opportunity to sort of reboot. What is your most aspirational vision of what a more positive harmonious world would look like? And what paradigm shifts of thinking and behavior would you most want to see?

Goodall: Well, first of all, I think we have to change this. There’s always a new development proposed, a new shopping mall, a new road, a new dam, a new whatever, and maybe that can lead to environmental destruction—that is less important. More important is this bottom line, and that has to change because as we destroy the environment, mother nature is actually screaming for help now. And as we continue to destroy nature, we’re destroying the future of our children, let alone the health of the planet.

Before lockdown, I was traveling 300 days a year around the world, and I saw with my own eyes what was happening. I stood in Greenland with Intuit elders and I watched that ice cliff, water pouring out, icebergs breaking off. And they said even in the heart of summer, this ice used not to melt, and this was spring. And I met people who’d had to leave their island homes because at high tide they were unlivable, especially in the storm, because sea levels are rising—partly because of all the ice melting and partly because as the waters heat up, they expand. And I’ve seen the aftermath of the terrible hurricanes, the typhoons, the flooding, the terrible, terrible droughts. And of course that is leading to these awful wildfires. I’ve got so many friends in California and Oregon and Washington state, and also in other parts of Europe where fires have been raging, Australia last year. And for the first time ever there have been fires in the Arctic circle.

One of the big problems, which is beginning to be understood, is that we really need to move toward a plant-based diet. And there will always be people eating some meat, and in some places where the land is unsuitable for agriculture, people only can live by having goats and creatures that can change grass into something that they can eat. But, by and large, as these billions of animals have to be fed, huge areas are cleared to grow the grain, then lots of fossil fuel is used to get the grain to the animals, the animals to the abattoir [slaughterhouse] and the meat to the table. Water, which is becoming scarce, fresh surface water in some parts of the world, an awful lot of water is used to get vegetable to animal protein. And then on top of all of that, all these billions of animals are producing methane gas, which is a very virulent greenhouse gas. So people are thinking about controlling emissions to mitigate climate change. Yes, we must control emissions from fossil fuel, but also the methane from all this animal agriculture is another really important aspect. So something we can do is eat less meat or no meat or be a vegan even, as long as people do something and think about it.

Schnall: Well, I just want to let you know that my whole family is vegan, which I was encouraged to do by my two daughters, for those very reasons that you just outlined. With all of the concerning things we face right now, I do feel like there is growing awareness about environmental issues, about societal issues on a level that I haven’t seen in awhile. Are there positive signs that give you hope that you see right now among all of the alarming problems we face?

Goodall: I see many signs of hope, and I think there’s a window of time we can mitigate climate change. During the height of lockdown, people living in big cities had the luxury of breathing clean air for the first time because of the factories that were shut down, less traffic on the road. They could look up at the stars and see them shining brightly, not through a haze of pollution. Hopefully there’s a groundswell of people not wanting to go back to the old polluted ways. In some countries, they can’t do much about it; in other countries, they can.

Jane Goodall and Roots & Shoots members in Santa Marta, Colombia, release sea turtles. | JGI ROOTS & SHOOTS COLOMBIA

And I think my greatest hope really lies with youth. You just said you were vegan because of your children. Well, I started this program Roots & Shoots back in 1991 in Tanzania with 12 high school students. The message: every one of us makes an impact on the planet every day; choose wisely; choose ethically. Every group choosing three projects: one to help people, one to help animals and one to help the environment. And that program is now in 65 countries. It’s got hundreds of thousands of members from kindergarten through university, and they are influencing their parents and grandparents. This program lets them choose their projects, and once they know the problems, they are empowered to take action. We listen to them, their ideas, their voices, and they’re changing the world. As we speak, they’re changing the world.

Schnall: Well, I’m so happy to be able to tell you that my daughter Lotus is a proud participant and grantee of the Roots & Shoots program. What is it that you most notice about youth activists today, and why is that so important to you? We often hear that children are the future, but as my daughters always point out, they are the voices of right now, and we need to listen to them.

Goodall: For many, many years there wasn’t this awareness about what we’re doing to the planet. I mean, when I began studying chimps in 1960, the forest was still stretching right across Africa; Gombe was part of those forests. We hadn’t caused the amount of damage to cause the kind of effects that we’re seeing now. But gradually, with Roots & Shoots and other programs like it, it’s being taught in more schools about the environment. So children are becoming aware. They weren’t aware before; they weren’t told anything about it. But now they’re aware, and we give them the opportunity to choose what to do, or they even demand it. I know many parents say, “I have to recycle because of my kids. I have to pick up litter because of my kids. I have to do this, that and the other because of my kids.” So they’re rising to the challenge because they have the understanding of the problems, which children before did not have.

Schnall: I one hundred percent agree with you. Part of Lotus’s project is to write these children’s books to educate other children about the environment and wildlife. You just mentioned your trips to Gombe, and you and I spoke 10 years ago on the 50th anniversary of your arrival in Gombe, Tanzania, when you began your groundbreaking research on chimpanzees. How do you feel about that anniversary, and how has your thinking and work evolved since then?

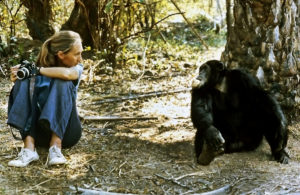

Dr. Jane Goodall with alpha male Figan at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. © THE JANE GOODALL INSTITUTE / BY DEREK BRYCESON

Goodall: Well, this year is the 60th anniversary. We’re learning more and more about the chimpanzees. And the great thing is, because it’s been so long, we’re onto the beginning of the fourth generation, so you can actually look at the effect of different kinds of maternal behavior. We now know who the fathers are because we can analyze DNA from fecal samples, so we can look at the personality of the father, as well as the mother. How, if the young ones know who the father is, I don’t see how they can, yet here’s some evidence that they seem to be attracted to those males who are their fathers, but we have no idea how. The work has evolved into bringing in some of the high-tech, to bring in DNA sampling, for example.

And then I think the biggest change is, the reason I left Gombe in ‘86 is because I realized that right across Africa, chimpanzees and forests were disappearing, and I felt I had to try and do something. And I went to six different range sites to learn more about what was happening to the chimpanzees and what their problems were. I learned a lot about it, but I also learned about the plight of so many people living in and around chimpanzee habitat. And that all came to a head when I flew over the tiny 35-square-kilometer Gombe National Park, which had been part of this great forest. I looked down in 1990 and saw a little island of forest surrounded by completely bare hills—more people living there than the land could support. And that’s when I realized, if we don’t help these people find ways of making a living without destroying their environment, we can’t even try to save the chimps.

And the Jane Goodall Institute began a method of community-based conservation, which we call Take Care or TACARE [Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education]. It’s very holistic. Basically, what began in the 12 villages around Gombe is now in all 104 throughout the chimp range in Tanzania, and it’s empowering the local people and giving them the tools, like using smartphones to monitor the health of their village forest preserves. They’ve become our partners in conservation. And so the forests have come back onto those bare hills. People are finding ways of living more in harmony with nature, and that program has expanded to six other African countries. If there was time to go into it, it’s a really fascinating program. I think it’s on JaneGoodall.org.

Schnall: Absolutely. I would encourage everybody to check out the amazing groundbreaking work of all the programs of the Jane Goodall Institute. In addition to the 60th anniversary of your visit to Gombe, Tanzania, this year is also the Centennial of the 19th amendment of women of winning the right to vote, which then, of course, took many decades for all women to receive that same right. As a female trailblazer, how do you view the progress that women have made, or have not made, toward gender equality?

Goodall: Well, it very much depends on the country that you’re in. Some countries are much, much more advanced than others. When I was 10 years old, I dreamed of going to Africa, living with animals and writing books about them. And everybody laughed at me. “How will you do that? You don’t have money, Africa’s far away, and you’re just a girl.” But I have this amazing mother, she’s always with me still. And she just said, “If you really want something like this, you’re going to have to work really hard, take advantage of every opportunity, and then if you don’t give up, maybe you’ll find a way.” And that’s the message I take to young people, particularly girls, particularly in disadvantaged communities around the world.

So I have seen enormous change in the developed countries, yes, but in Tanzania, for example, we’re providing as many scholarships as we can to keep girls in school; other organizations are doing the same. And women are staying for secondary education, some going to university. So it really has changed a lot. There are women in high up places in government, and in other countries, it’s beginning to be more equitable. I always love this Indigenous person from Latin America, it was a chief, and he told me his tribe was like an eagle. He said, “One wing is male and the other wing is female, and only when they’re equal will the tribe fly high.” And I love that. That’s what we should aim for: equality. Because when the women’s movement first began, the women who got to the top did so by using the characteristics of males—really aggressive and dominating and strident and forceful. But men and women have different qualities, and we need the slightly softer approach of women, which I think has come through evolution because our job in evolution was to raise children. And to be successful in that, you have to be understanding and compassionate and listen to them and learn to understand the needs of a little baby before it can talk. And you need to be able to kind of mitigate the quarrels within a family. So we need the two qualities. They’re both important.

Schnall: I one hundred percent agree with that. And it reminds me of something you said to me when we spoke 10 years ago, when you were also talking about how you felt we’ve lost wisdom and the problems that we face when we disconnect our head from our heart. What hope do you have? Or what signs do you see that humanity’s consciousness can and will evolve?

Goodall: I see changing attitudes around the world. There have been huge advances in many, many countries in legislation as it relates to animal welfare—things that you wouldn’t have dreamed could possibly happen 10 years ago. I mean, just last week in China was the very first prosecution of the owner of a dog who abandoned it. We wouldn’t have believed that 20 years ago. And this legislation in South Korea about breeding dogs to eat, and in the United States, a lot of bills are being proposed, whether they go through or not is another matter, but requiring stiffer sentences for cruelty to animals. And then understanding that animals are not on this planet for us to use and abuse—that we need to be able to live in harmony with them. It was Mahatma Gandhi who said, “You can judge your nation by the way it treats its animals.” And I think many nations, if they were measured by that standard, wouldn’t score very high right now.

Schnall: With all of the many mounting problems that we face, it’s very easy for one person to feel like there’s nothing they can possibly do can make a dent or make a difference. What advice or encouragement would you offer?

Goodall: One thing we’re hearing all the time is, “Think globally, act locally.” But turn it around, because, quite honestly, if you read the newspapers or watch the news around the world, you can’t help but feel depressed. It is depressing. There’s an awful lot of really bad things happening politically, socially and environmentally. But instead of just feeling helpless and hopeless, which is what happens, say, “I’m here and now, in this place. There’s a dirty stream. I can get together with my friends. We can clean that stream up.” And then the water that goes into the river will be clean, and then there are other groups cleaning other streams, and that river is going to get cleaner and cleaner. And there are groups of people fighting the plastic pollution, trying to stop the plastic getting into the rivers. And by the time the rivers are clean, that will help the pollution in the ocean.

Do the projects that you can do locally. You can go and volunteer in a shelter. You can volunteer in a soup kitchen. You can raise money to help the children. There are 200,000 malnourished children in Puerto Rico as a result of hurricane Maria all those years ago, and all that President Trump did at the time was to go and throw out paper towels. And now some money has gone to them that should’ve gone three years ago. There’s an awful lot of things that we can do locally, and it makes you feel good—you’ve succeeded in something, you’ve done something, you can see the results of it. And then when you know that there are other people just like you doing the same thing, then what you’re doing is multiplied and multiplied and multiplied, and changing the world. And then you have hope.

Schnall: Absolutely. In these intense times, and these are particularly intense times, especially when you’re someone like yourself who feels so called to spread your message and be out there facilitating change, how do you practice self-care? How do you keep yourself centered and energized and positive in all of this? I think we’re all looking for guidance on that right now.

Goodall: Well, I do try to live in the moment. From the beginning of the pandemic, I’ve been in lock down, basically. I luckily was caught here in the UK, in the house. This is the house I grew up in—books behind me, many of them I had as a child, and out of the window, there’s the tree of which I used to spend time as a child. And there, two streets down, the hotel where I worked as a waitress to raise the money to go out to Africa in the first place. So when I first was grounded here, I was frustrated and angry, but then I thought that’s no good. So with the Jane Goodall Institute team, we created “virtual Jane,” and virtual Jane sits here in this tiny little room. I sit here, and I can reach out to people around the world, and I get messages back. That helps me to keep going, because it’s much, much more exhausting than it was traveling 300 days a year. Just sitting here, I don’t have the fun of meeting my friends and having nice evenings with them and maybe going out into some new piece of environment and meeting people’s dogs and all that kind of thing. So it’s just focused on what you’re doing and getting feedback that it’s working. I’ve had the chance of reaching millions more people in many more countries than I could have if I’d just been doing the tour. So it’s not the same.

And the hardest thing for me is I have to give talks. And when you give a talk in an auditorium, there’s a lot of energy out there and there are maybe thousands of people, and they’re listening to you and they’re laughing at jokes and they’re applauding and it’s live. It feeds me. It gives energy to me. Now I’ve got to try and imagine that I’m looking at a little green speck of light that’s the camera and trying to create energy from that. That’s what I’m always very happy when people write and say, “I was very inspired by your talk.” I think, Phew! Thank goodness for that, because it’s really difficult.

Schnall: You are a historic trailblazer; you’re a role model. You have done so much transformative work and positive change in the world. What do you hope your legacy is? And what is the enduring message that you hope to pass on to future generations?

Goodall: There are two bits of legacy that I want to leave, in addition to creating an endowment so that the 24 Jane Goodall Institutes, as well as Roots & Shoots in 65 countries—I don’t want the work that we’re doing, which really, really is making a positive impact, to dissipate when I go. So there needs to be an endowment that can support a small group when it’s in difficulties and can’t raise its own money, but that’s separate.

The two things I really am hopeful that will be thought of as my legacy: One is starting Roots & Shoots because that is changing lives. And the other is helping people, including scientists, to admit that we’re part of the animal kingdom, so that we look at animals in a different way and treat them more humanely, more compassionately. Those two things.

And the most important message is: remember that every single day, every single one of us makes an impact on the planet. And we can choose what to buy, what to wear, what to eat. Unless we’re in real poverty. And we have to alleviate poverty because if you’re really poor, you’re going to cut down the last trees because you’ve got to grow food to feed your family. You’re going to fish the last fish for the same reason. If you’re in an urban area, you’re going to buy the cheapest junk food. You can’t afford to say, did its production harm the environment? Was it cruel to animals? Is it cheap because of inequitable wages paid to people? You just have to survive. So we have to alleviate poverty. We have to think about each of our environmental footprints every day.

And we do have to actually admit that right now, the 7.2 billion of us, already we’re using up natural resources in some places faster than nature can replenish them. They’re saying there’s going to be closer to 10 billion in 2050. I don’t know what’s going to happen, but we can’t just ignore this. And just to mention, it is sometimes perceived, I’m told, as condemning the people living in poverty, who actually are not responsible for the climate change, that we, the affluent, are causing. It’s nothing to do with that. It’s just that as we raise people from poverty and they all yearn for the unsustainable lifestyles we have, what’s going to happen? I don’t know.

Schnall: What is your one message or call to action?

Goodall: To think about what you do every day and to make ethical, compassionate choices in what you eat, what you buy, what you wear. And just realize that it’s not you alone—together, collectively, we are making a difference. And there is a window of time, but we’ve got to get together and take action now.

Schnall: Thank you so much, Jane, for all of the work that you do and all of your wisdom. We need it now more than ever. I’m sending you good thoughts and huge gratitude for your amazing trailblazing work, which is making a difference.

Goodall: Thank you very much. And say hello to your children for me.

For more information about the Jane Goodall Institute and its programs, visit janegoodall.org

Marianne Schnall is a widely-published interviewer and journalist and author of What Will It Take to Make a Woman President?, Leading the Way, and Dare to Be You. She is also the founder of Feminist.com and What Will It Take Movements.

This interview originally appeared at ForbesWomen.

Visit COVID Gendered for more articles, information and resources.

Marianne Schnall is a widely-published interviewer and journalist and author of What Will It Take to Make a Woman President?, Leading the Way, and Dare to Be You. She is also the founder of Feminist.com and What Will It Take Movements.